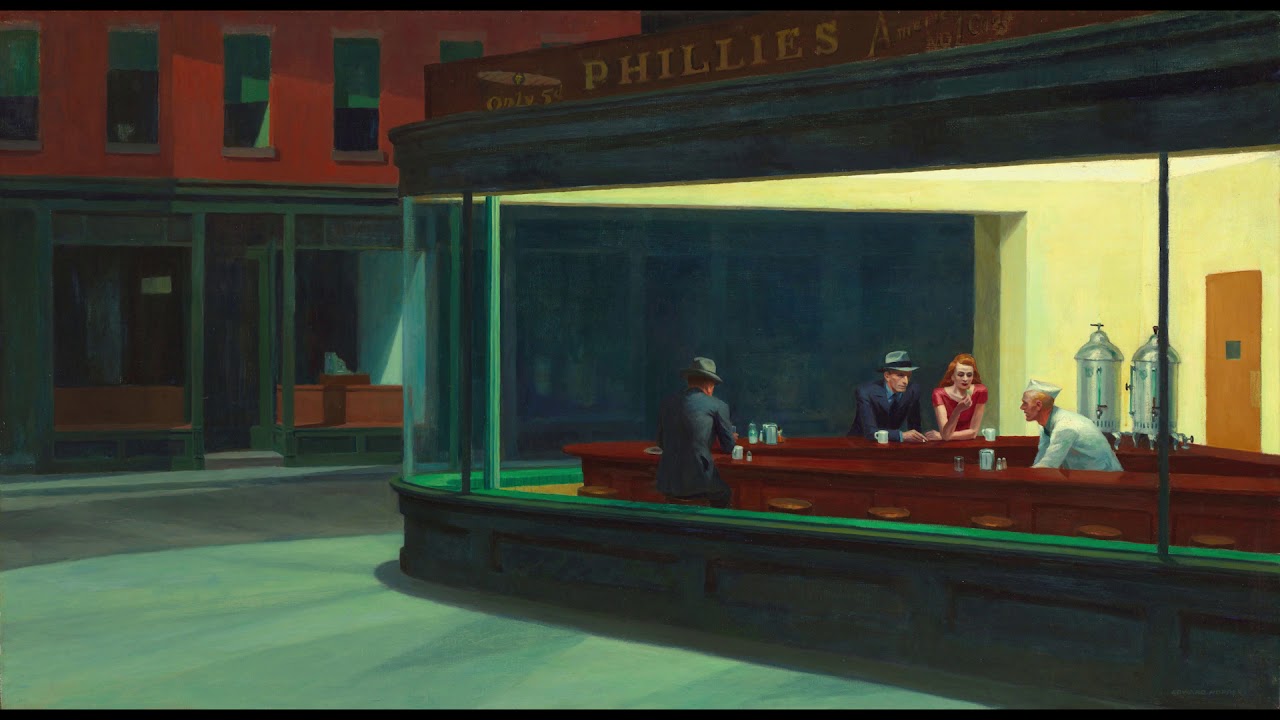

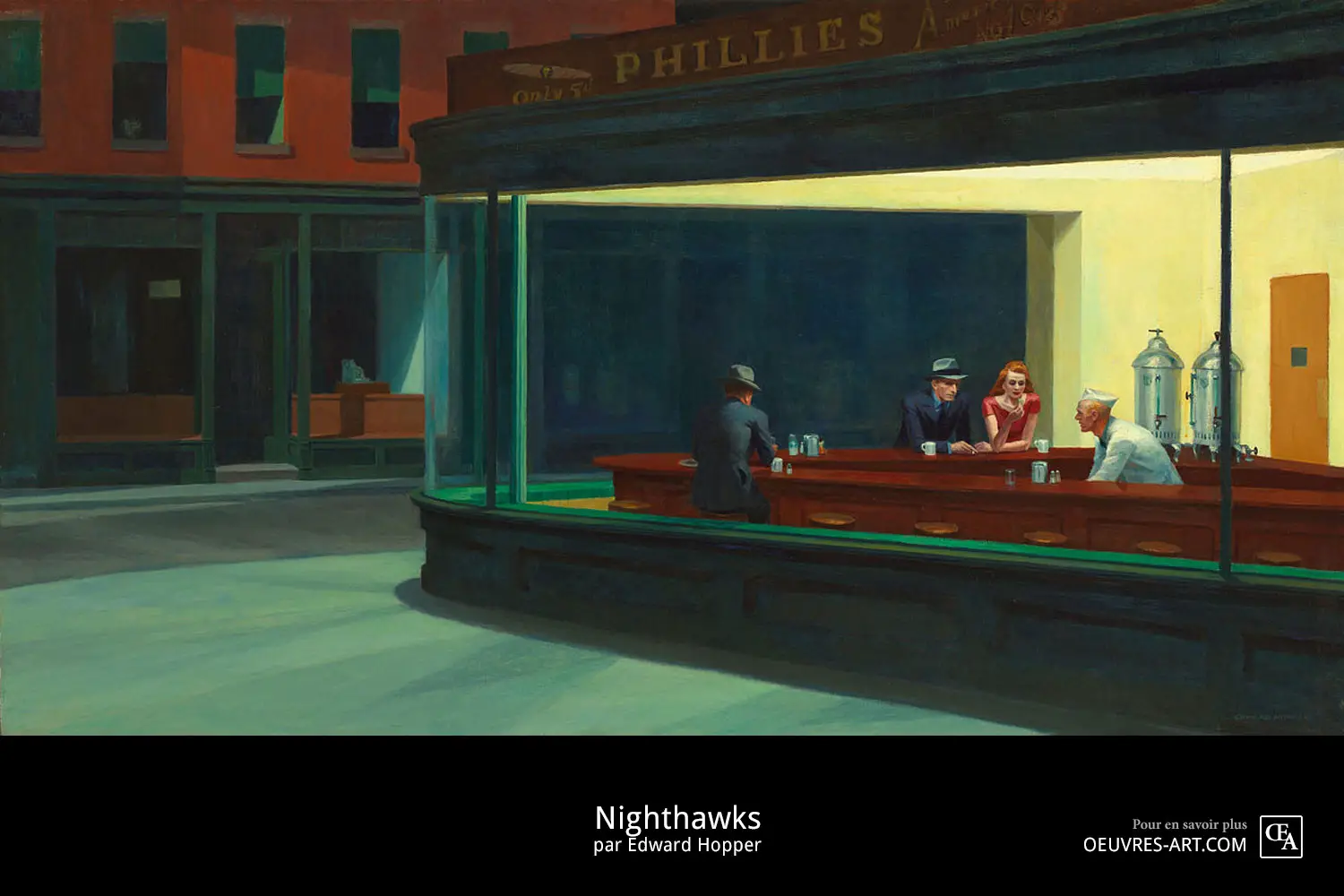

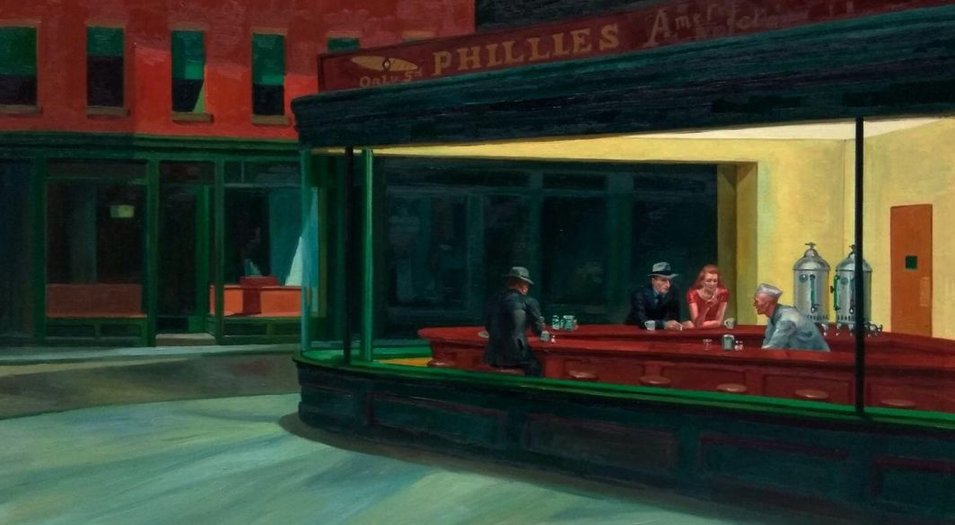

The famous painting offers a crucible of narrative potential, capturing the melancholic romance of city life: its endless possibilities-and inevitable failures-for connection. Bright overhead lighting casts a theatrical play of shadows on the deserted sidewalk outside, with the sleek, curving form of the diner’s long window intersecting with the grid of storefronts behind. Solitary, hunched figures perch on stools along the slender countertop of an all-night diner. In the 21st century, the museum should not be a place that blindly reinforces the lack of context typical of social media, but rather should use the breadth of its collection to add depth to our digitally informed ways of seeing, especially when that complication reveals the participation of underrepresented identities.For an image so often associated with loneliness, Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942) is strangely seductive. (Furthermore, Hopper’s success was not his alone - his wife Jo Nivison Hopper gave up her own art practice to support her husband’s career.)

Together they reveal that Hopper was not a lone genius, but rather a man among many others tapping into a common unease interpreted by American artists of all kinds. Hughie Lee-Smith, “Desert Forms”(1957) at the Art Institute of Chicago Psychologically, the work of both Abercrombie, a Chicago Surrealist who explored placelessness in her work, and Lee-Smith, who used Surrealist displacement as a tool for communicating the anxiety of being a Black man in America, enhance the otherworldly isolation of “Nighthawks.” Whereas before “Nighthawks” may have felt lonely, in the presence of these pendants it now feels almost threatening. Gertrude Abercrombie, “The Past and Present” (c. On a formal level, motifs are mirrored across the paintings: a white vase in the Abercrombie rhymes with a ghostly cash register in the shadows of a closed storefront in “Nighthawks,” and the faceless figure at Hopper’s counter is mimicked in Lee-Smith’s mystery woman, whose back is also turned to us.

As a pseudo-triptych, they paint a portrait of figurative art at midcentury that fleshes out just who took part in that movement, and how each artist added to it. With no heavy-handed explanatory text, the museum allows the works to speak for themselves, and, perhaps more importantly, to speak to each other. This new setting, where it is flanked by oil paintings by the (woman) artist Gertrude Abercrombie to the left and the (Black) artist Hughie Lee-Smith to the right, seeks to undermine the “art system,” as Reilly puts it, as “an hegemony that privileges white male creativity to the exclusion of all Other artists.”

Before the rehang, Edward Hopper, “Nighthawks” (1942) at the Art Institute of Chicago (image courtesy Wuselig via Wikimedia Commons) The change - which took place on March 4 and had the painting moved from its place alone on a freestanding wall at the center of a gallery to hanging between two paintings on the far end of another - is noted only on the gallery map, for the clarification of the habitual visitor.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)